Article by Gemma Carroll, PNZ Communications & Extension Officer, based on a report prepared by Waka Paul, Social Scientist, Plant and Food Research Institute.

Understanding growers and agronomists needs and goals in nutrient management, is a key focus of the Sustainable Vegetable Systems (SVS) programme in order to develop deeper understanding and to enable improvements for better environmental, and in turn, economical outcomes.

The findings from grower interviews and focus groups help inform SVS team thinking and output design.

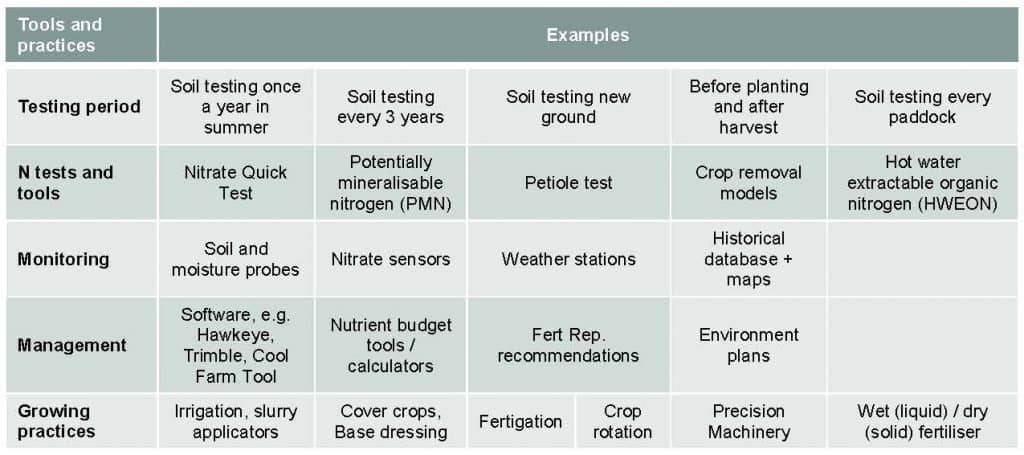

Growers and agronomists use a variety of tools and practices to gain a better understanding of what is happening in the soil and the volume of nutrients required for their crops. Crops, tools and practices are affected by factors such as location and geology. Growers gave decision-making factors that included: soil type and profile, e.g. having clayish soils, having a high level of naturally present phosphate and land susceptible to wet weather conditions. Participating growers and agronomists identified several strategies that they are currently using for assessing N and other nutrients in their growing system.

Growers indicated that they are seeking quick results to fit the pace of their own production system decisions and that tools that require a lot of effort can be difficult to work with and off-putting. “No grower wants to wait two weeks to get a soil test result back for nitrogen”. “A 6-week wait is too long”.

There are some uncertainties around depth and size for soil tests, which you can read more about in the full report. Regarding size, “growers are sceptical about how a teaspoon of soil can give you a representative sample of your whole paddock”. Growers do not want to miss out on information available at deeper levels that they feel could improve their nutrient management practices. For that reason, nitrate quick tests were considered an important solution. “Cropping guys want something easy and that is why we’re really pushing this quick N test as a solution … For any deep-rooting crops we go down to 30cm, and any winter or shallow-rooting crops we go down to 15cm”.

Opinions on the effectiveness of the Nitrate Quick Test varied from growers/agronomists depending on soil profile and region. “We’re working with some pretty heavy clay around the farm. Leaving samples just to set by gravity didn’t work for us so we bought a centrifuge and I definitely recommend it if using the quick N test”.

Physical exertion of the test process is also a factor, which has led to some growers using alternatives such as petiole testing to get a better understanding of nitrate levels. In some regions a synergy is adopted between different methods. For example, both the Nitrate Quick Test and a centrifuge. For adoption of any new tool or practice it will be important consider whether it is a standalone tool/practice, or if it comes packaged with other tools/practices to optimise effectiveness.

The cost of testing and specifically targeting nitrogen were also issues raised. A grower in the Canterbury region felt that it was better to test for phosphates and to some degree magnesium in his region, as nitrogen testing results can be inconsistent. A similar sentiment expressed in the Pukekohe region: “every paddock we have soil tested, but not for nitrogen because we have found it unreliable and hard to interpret.”

“You can’t soil test every five minutes and foliar test every five minutes; it is too expensive”.

“We do tests once every three years. We don’t have enough resources to sample everything once a year.”

One resource growers have plenty of, is the knowledge they have gained through years of working with the environment. Every grower and agronomist interviewed has been in the horticulture industry for at least 5 years, with many having been involved in vegetable growing in some form for 10 or 20 years.

This reliance on historical data when it comes to decision making was a common message throughout the discussions and reflects the earlier SVS baseline survey, which found that 58% of growers surveyed rely on their own historical knowledge to inform nutrient/fertiliser decision making (FOLKL 2021, p. 10). As one agronomist noted, “We do a nutrient budget but I’m finding that most of the applications are occurring based on historical preferences as opposed to what we say they require, particularly nitrogen”.

Crops, tools, and practices have continued to transform as more knowledge becomes available on topics such as plant needs, sustainability, and fertiliser application rates, and as the quality of the fertiliser, tools and practices used also sees improvement.

“When it affects your business and affects your profit, you learn in a hurry that this is not what you do”.

Gross margin and bottom line were common drivers among all participants when it came to nitrogen use and general nutrient management. Many expressed a concern with the overuse of nitrogen due to its effect on quality, yield, and the ability to meet consumer demand.

“There are no shortcuts when it comes to nitrogen use. A lesson that has been learned the hard way for several growers. […] We can’t afford to put on more than we need because it is costing us money”. No matter how much tonnage achieved at harvest, “if the quality is not there, it costs more to sort out the good produce from the bad produce.” Whether it be the effect it has on crop quality or the effect it has on profit, many of the growers interviewed commented on the dangers of the misuse of nitrogen.

Being compliant with environmental regulations and satisfying the market by proving to be more sustainable in practice are also key drivers in grower decision-making. A message expressed across all five regions. Just as the crops and technologies have changed, so too have attitudes towards growing practices and environmental sustainability. “Things have certainly changed in terms of nutrient management from 15/16 years ago. Whether it is growers or service industries or whoever, they are much more aware of environmental concerns and strategies for mitigation are right up there”. There is however concern with how sustainability is measured, and that perhaps not everyone has the same understanding of sustainability. “What exactly is efficiency? People are defining it in different ways” yet “we do understand [that] as growers we need to look after the environment”.

The development of any new tool or practice in nitrogen management will need to bring not only growers on the journey of change, but also industry, policy and even markets to gain the consistency of messaging and communication to support grower confidence to engage and adopt.

Both growers and agronomists signalled a keenness to use new tools and/or practices if they helped in the better use of nitrogen and were able to identify the best practices that would help achieve environmental sustainability. These tools and/or practices must first be proven and need to be able to help growers strike a balance between understanding the volume of nitrogen in the soil and meeting consumer demand. A capability that requires a lot of trust.

The findings from the interviews and focus groups goes on to reveal the challenges of trust-building and confidence in both the tool(s), new practices, the science behond them and the new regulations. There is an eagerness to try and solve this dilemma but convincing growers that more is not always the best decision has been a challenge for agronomists: “The quicker I can give someone an answer backed by data, the better I’ll be able to convince them to reconsider applying more fertiliser because the data suggests otherwise”.

“The most complex thing about growing nowadays is not the growing. It’s having to deal with all the rules and regulations”.

The biggest question marks for those interviewed were around understanding nitrogen mineralisation, understanding nitrogen availability, understanding cover crops and organic matter, and how to accurately measure what is left in the soil. Calculating the level of nutrients available after a harvest was a key issue for growers in the Canterbury region. “Estimated average for what is left behind is quite difficult because we have quite a wide harvest window for many of the crops […] Say you bypass a patch of green vegetables because it just doesn’t look good enough for the consumer. By the time you finish, you just have no idea what is left in the paddock”. There is where the concurrent work in the N-Mineralisation project (PNZ-85) will be of benefit to SVS.

There is also interest in better understanding the impact temperature, aeration and moisture levels have on growth in the wake of cultivation activities. “If you cultivate a paddock and the temperature is right, you’re going to get a flush of growth after that cultivation, and whether that’s due to increasing soil temperature or aerating of the soil, or reducing soil moisture content, I don’t know” (Hawke’s Bay agronomist).

SVS research is making the invisible visible, and developing a tool that is easy to use, integrate into existing systems and enable timely decision making is pertinent.

Now that growers and agronomists have started this conversation around better nutrient management, it is important that they continue to be involved in the process. SVS are working with Folkl Researchers on upcoming deep-dive focus groups. If you would like to be involved, please contact Trzzn.Pneebyy@cbgngbrfam.pb.am

SVS project reports can be found here https://potatoesnz.co.nz/rd-project/emissions-project/

SVS updates and bulletins are found here https://potatoesnz.co.nz/research-and-development/research-updates/